In an autobiography, one writes his own biography. Here I will interview myself as an investor in order to express my views and share my mindset. I will start with general questions and move to more particular ones as the interview progresses.

What do you do?

I am an investor.

What do you invest in?

I invest in businesses trading on the stock market, stocks.

And what do you look for in a business before investing?

I require the price of the stock to be materially lower than my calculation of its intrinsic value.

What’s intrinsic value?

It is the present value of the cash flows a business will generate over its lifetime.

Interesting, and does the company give you that number if you ask?

No, you have to calculate that yourself.

And how am I supposed to do that?

You have to calculate the true economics of the business over time.

Meaning?

Well, first you have to know a business intimately. How is it likely to perform considering the type of business it is? What is the quality of management and what are their plans? Are current financial figures indicative of its true business economics? What is the business model? How does the business create (or destroy) value over time and at what rate do you expect it to continue to do so?

Considering that, have a view of the cash flows you reasonably expect the business to generate going forward. To do that you need the cash they put in the business as well as what they get out. Then you have to take those future net cash flows and discount them back to the present day.

Discount them?

Yes, discount them. A dollar today is worth one dollar, but what is a dollar worth today if you get it next year or in 5 years? This concept is known as the time value of money.

Ok, got it.

And the likelihood that you will receive those cash flows should factor in your intrinsic value calculation. For me, a high quality business has a high probability in getting those cash flows and vice versa. That is how I understand quality.

But not all cash flows are made the same - rates of return differ. That means a company which requires less capital to grow is, on average, worth more than one which requires more capital.

How do you mean?

Well, if a company can invest capital at a 10% return and another one can do it at 20% - which one is more valuable?

The second one.

Yes, but if the company that invests capital at 20% has a shorter runway for growth than the company that invests at 10% - the future value calculation starts to look very different.

The 10% return company will possibly catch up to the 20% return company and surpass it. This is simple maths, but not simplistic.

What if something happens to the business and the return on that capital goes up or down?

That’s a very good point. To understand these fluctuations, the type of the business and its quality is a good starting point.

A business which is cyclical has by definition, more uncertain cash flows than a business which isn’t. And if that company has debt, it makes it extra hard to calculate those cash flows.

A non-cyclical business has less volatility in cash flows which makes it easier to calculate. However, business risk is always there - you can never ignore it.

Business risk is when a company goes under?

Not necessarily. I don’t view business risk as binary - I view it as any negative development for the business which influences its ability to create value going forward.

This development affect its competitive position and causes its business and profitability to decline. When that happens, chances are high that you will lose money on your investment.

Can you give me an example of some business risks?

Sure, they are all around. The most evident ones come from legal and regulatory changes. But disruption is also a big one - think physical retail being disrupted by online commerce, think technological advancements, think cyclical and secular shifts.

Kodak and IBM were all high flyers which were never questioned as future leaders by the market.

Maybe it was confirmation bias, the recency effect, or the structure of institutional investing - I don’t know. Most weren’t able to see the destiny of those businesses.

But business risk is just one of the risks you need to look out for. You also need to be mindful of not overpaying for a business.

For example?

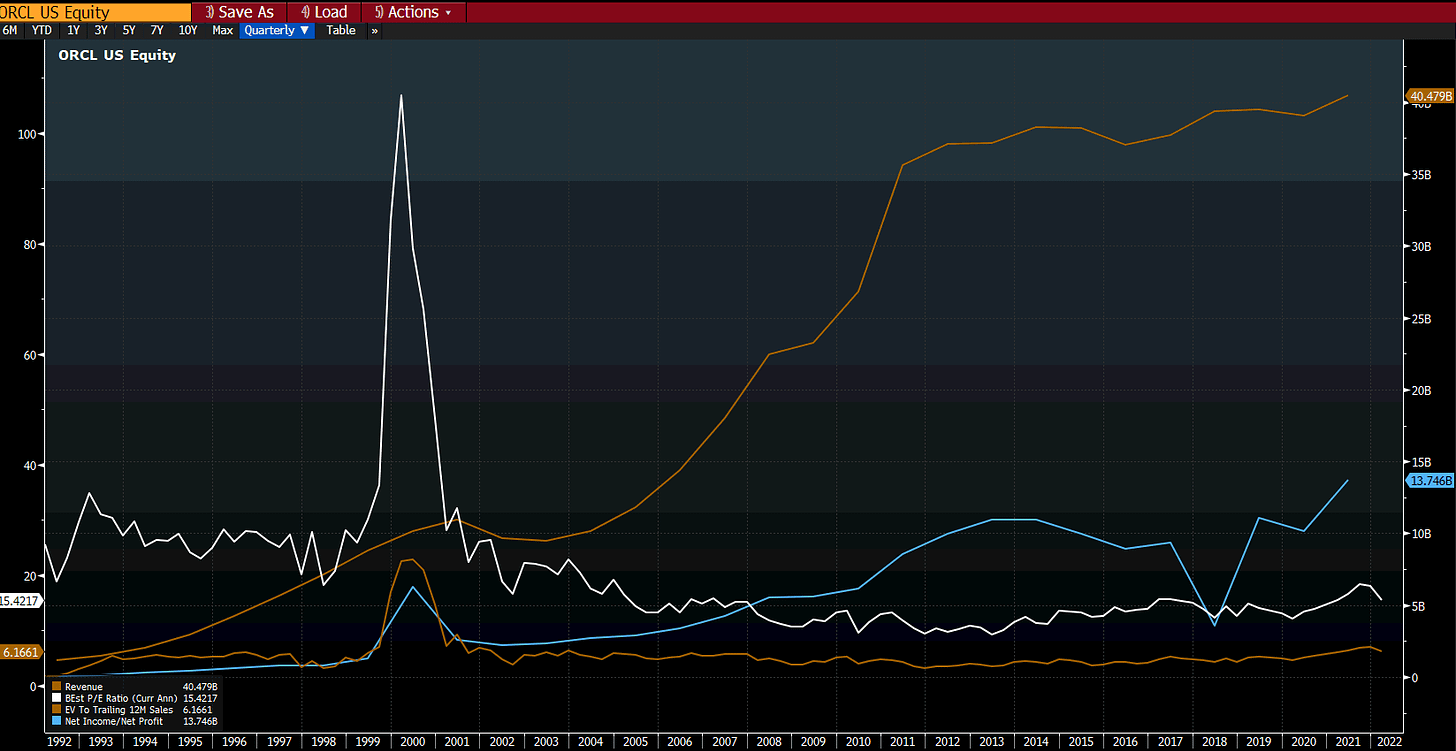

Look at Oracle, a great business growing every year. But it took the share price 15 years from the highs of the 2000 tech boom to recover its value. Investors simply overpaid for the business and had to suffer for it.

The business is one thing and the stock is another - even though over long periods of time the two converge.

Please simplify! 😳

Well, in 2000 the market was paying $100 for each $1 of earnings (100x earnings). After the tech bust, the market was only willing to pay $15 to $20 for each $1 of earnings.

The business continued doing very well after the bust, but it took the stock 15 years to reach its 2000 highs.

My point is regardless of value - price is also extremely important.

I read something about margin of safety, is this where it goes?

Yes! You have to pay a discounted price from your assessment of intrinsic value. The margin between the price you pay and the intrinsic value is the safety.

You require that safety to protect you from any negative developments or miscalculations from your part. The irony is that this discount also serves to increase your return from the investment because the lower the price the better right?

Sounds legit. But what if we are in a bear market and stocks are crashing, would you still buy those stocks?

A bear market or if a stock is making new lows or is at all time highs should not stop you from making intelligent investment decisions. In fact the best opportunities come at times of fear, uncertainty and doubt.

All these market-related realities have no bearing on intrinsic value. You have to be able to use the market to your benefit but at the same time disregard it.

Isn’t it better to own bonds during bear markets to avoid capital loss and earn some fixed income?

Look, I am a businessman. I am not in the business of lending money to people so they can do business themselves. Why would I do that? My upside is limited but my downside is not.

Besides, inflation will probably erode most of my capital over time if I invest in bonds.

I just thought putting some money in bonds would help reduce risks and volatility in the portfolio in case something really bad happens.

First, risk is not the same as volatility. Second, who says bonds protect you from bad things happening?

It may seem that way because bond markets move much less than stocks and because recent history has been very good for bonds.

But if you go back enough in history, you will find that fixed income investments have an open downside (full loss) with limited upside. Why would you do that? Just because of lower volatility?

So you see, volatility has nothing to do with risk. A bond which doesn’t move for 3 years could lose 100% of its value and a stock which moves wildly could create tremendous value going forward.

Isn’t high volatility equal to high risk?

That doesn’t seem to be the case. Risk stems from the relative price you pay for a business and the characteristics of that business. Not from how much a stock price has moved in the past year.

I understand. This means a stock that has dropped by 50% doesn’t have to be bad and a stock which has rallied by 100% doesn’t have to be good.

Yes, that’s exactly what I am saying. The stock market seems to be highly flawed in valuing equities correctly. The market is not independent of the fallible humans participating in it.

Our cognitive apparatus is primitive in many respects, and our emotional mechanisms developed to help us survive not thrive in investing!

As we are by nature social animals, social proof is an amazingly powerful force to go against. The market is not some all-knowing future-predicting mechanism.

And so you have to be very careful of confusing the short term with the long term.

So you’re saying the market is not efficient!

Spot on! The market is definitely not efficient. And your job as an investor is to benefit from those inefficiencies as much as possible.

How can I benefit from these inefficiencies?

I suggest you start reading about businesses and sectors and start to think like a businessman.

Quickly discard businesses that are uninteresting to you and ones which are hard to figure out. Focus deeply on those that you can.

Then when you have calculated the intrinsic value of those businesses, only buy at a price that gives you a forward long-term return that is worth the ride.

You’ve given me a lot to think of. Can I ask you a few more questions?

I think we’ve covered enough ground for now. Next time you can.

Thanks Philoinvestor.

Appendix

Key: The market is not efficient.

That’s why we have opportunities.